Berga am Elster:

American POWs at Berga

by Mitchell G. Bard

American Jewish soldiers had to decide what to do.

All had gone into battle with dog tags bearing an "H" for

Hebrew. Some had disposed of their IDs when they were captured,

others decided to do so after the commandant's threat.

Approximately 130 Jews ultimately came forward.

They were segregated and placed in a special barracks. Some 50

noncommissioned officers from the group were taken out of the camp,

along with the non-Jewish NCOs.

The Germans had a quota of 350 for a special

detail. All the remaining Jews were taken, along with prisoners

considered troublemakers, those they thought were Jewish and others

chosen at random. This group left Bad Orb on February 8. They were

placed in trains under conditions similar to those faced by European

Jews deported to concentration camps. Five days later, the POWs

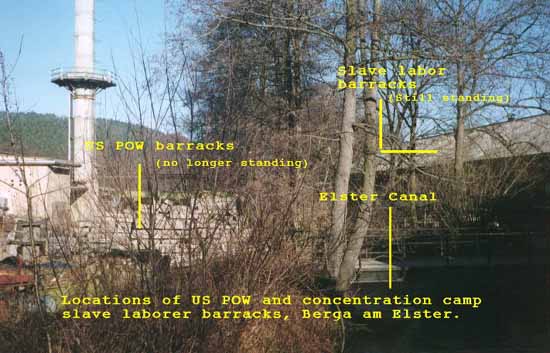

arrived in Berga, a quaint German town of 7,000 people on the Elster

River, whose concentration camps appear on few World War II maps.

|

Conditions in Stalag IX-B were the worst of any

POW camp, but they were recalled fondly by the Americans transferred

to Berga, who discovered the main purpose for their imprisonment was

to serve as slave laborers. Each day, the men trudged approximately

two miles through the snow to a mountainside in which 17 mine shafts

were dug 100 feet apart. There, under the direction of brutal

civilian overseers, the Americans were required to help the Nazis

build an underground armament factory.

The men worked in shafts as deep as 150 feet that

were so dusty it was impossible to see more than a few feet in front

of you. The Germans would blast the slate loose with dynamite and

then, before the dust settled, the prisoners would go down to break

up the rock so that it could be shoveled into mining cars.

The men did what they could to sustain each other.

"You kept each other warm at night by huddling together,"

said Daniel Steckler. "We maintained each other's welfare by

sharing body heat, by sharing the paper-thin blankets that were given

to us, by sharing the soup, by sharing the bread, by sharing

everything."

"Surviving was all you thought about,"

Winfield Rosenberg agreed. "You were so worn down you didn't

even think of all the death that was around you." He said his

faith sustained him. "I knew I'd go to heaven if I died, because

I was already in hell."

On April 4, 1945, the commandant received an order

to evacuate Berga. This was but the end of a chapter of the

Americans' ordeal. The human skeletons who had survived found no

cause to rejoice in this flight from hell. They were leaving friends

behind and returning to the unknown.

Fewer than 300 men survived the 50 days they had

spent in Berga. Over the next two-and-a-half weeks, before the

survivors were liberated, at least 36 more GIs died on a march to

avoid the approaching Allied armies. The fatality rate in Berga,

including the march, was the highest of any camp where American POWs

were held—nearly 20 percent—and the 70-73 men who were killed

represented approximately six percent of all Americans who perished

as POWs during World War II.

This was not the only case where American Jewish

soldiers were segregated or otherwise mistreated, but it was the most

dramatic. The U.S. Government never publicly acknowledged they were

mistreated. In fact, one survivor was told he should go to a

psychiatrist. Officials at the VA told him he had made up the whole

story.

Two of the Nazis responsible for the murder and

mistreatment of American soldiers were tried. They were found guilty

and sentenced to hang, despite the fact that none of the survivors

testified at the trial . Later, the case was reviewed and the

verdicts upheld. Nevertheless, five years after being tried, the

Chief of the War Crimes Branch unilaterally decided the evidence was

insufficient to sustain the charges and commuted the sentences to

time served — about six years.

No comments:

Post a Comment